20 - The Prototype and the Rulebook

20 - The Prototype and the Rulebook

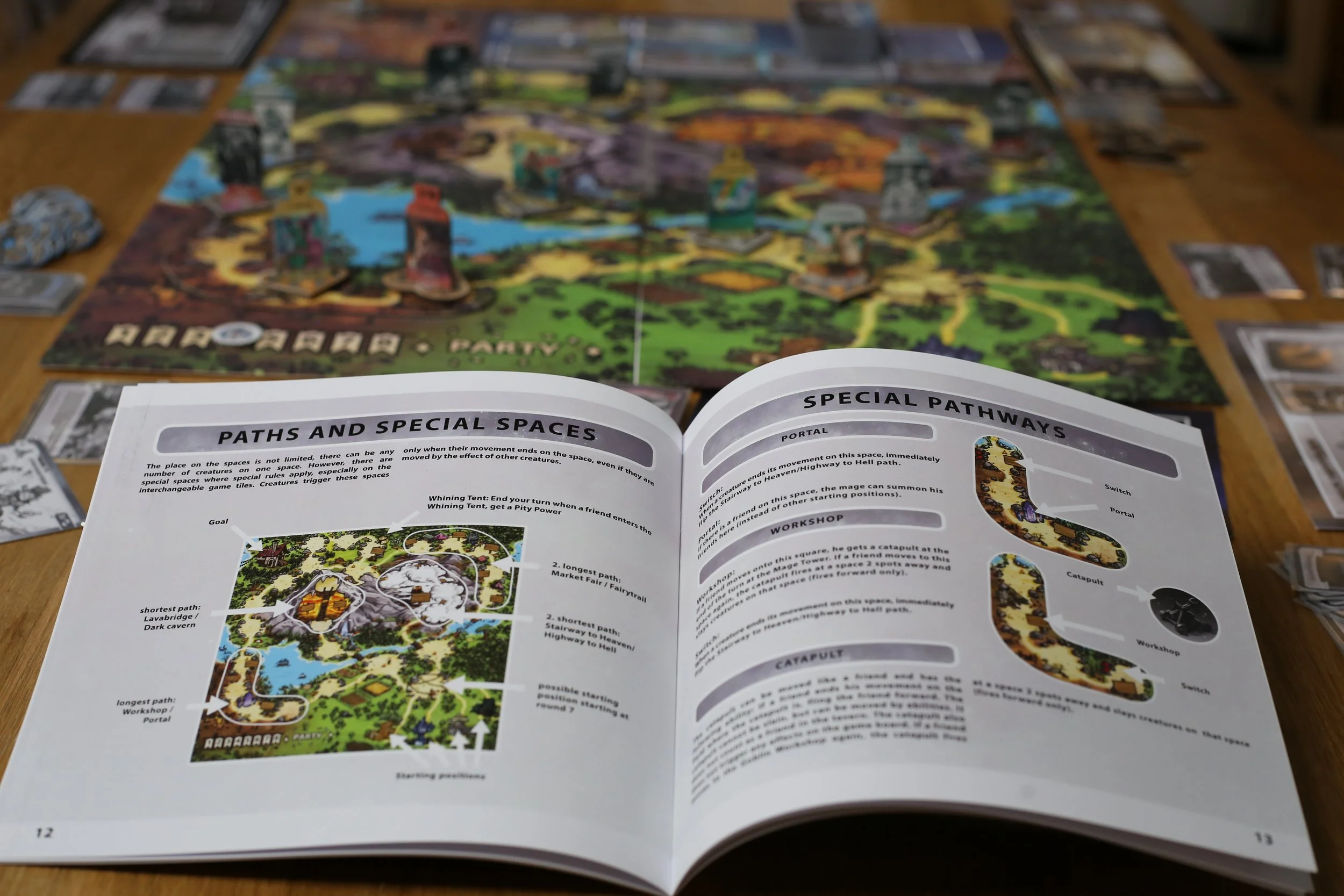

Even though the rulebook is usually ignored after the first few games, it is an extremely important part of any game.

Unfortunately, it’s also a part that requires a lot of work — especially if you don’t particularly enjoy writing … and if you plan to publish the game in two languages.

The earlier you write down a meaningful rulebook, the better. On the one hand, the game can then be tested without a personal explanation. On the other hand, it’s not only the game that needs testing, but also the rules themselves. If the rules are interpreted incorrectly, the game will be played incorrectly, and the playtest becomes only partially useful.

A written rulebook is often much longer than the usual verbal explanation of the rules. The quick clarifications you can answer with a simple “yes” or “no” during an explanation also need to be addressed in the written version.

There are several helpful tips online about how to write board game rulebooks, and it certainly doesn’t hurt to look through them.

It’s definitely useful to study rulebooks from games where you personally feel the rules are well explained. But going through the rules of very well‑known games isn’t a bad idea either. You’ll notice a common structure that board gamers are already familiar with.

It’s also helpful to think about the structure of your rulebook — in what order should the game be explained? Sometimes it’s beneficial to repeat certain rules. For example, it doesn’t hurt to mention the game’s objective early on, but it’s also useful to repeat it again during the final scoring section at the end of the rules.

After the first few plays, the rulebook is mostly used for reference. Can players find information easily? Are all questions answered?

These are questions only testers can answer for me. Since all of this is not easy, it’s also difficult to reach a point where you can say: “Okay, this version of the rules is good/pretty enough to share.” Too many errors mean the rules aren’t very helpful and can frustrate testers. But without testers, you won’t discover many mistakes or opportunities for improvement. And when do you hand everything over to an editor? There will be many versions of the rulebook.

The rulebook for Magical Friends has already gone through many revisions, but now you can finally view it online. On the landing page, you can download the PDF if you like. I’m very happy about any feedback — but I’ll warn you in advance: there will probably be many more adjustments before it goes to an editor, and of course many images will still be replaced.

Are you also working on a rulebook? What problems have you encountered? If you take a look at the rules, your feedback will definitely help me improve them. Every tip is appreciated!

Update: Now that the game has been published, the rulebook is definitely the number one thing I want to improve for a second edition. ;-)

19 - Call to Action

19 - Call to Action

One of the most important parts of advertising is the “call to action” — the invitation to do something. At the same time, it’s also one of the most difficult parts for me personally. Ads that include a call to action are much more effective than those without. If you look up “call to action,” you’ll quickly find plenty of articles on the topic.

Such a call might be asking the reader or viewer to subscribe to a newsletter, like a post, follow a page, buy a product, or simply join a discussion. It’s an invitation to participate or a request for support. Someone who might not have thought about supporting a product or who doesn’t yet feel part of the community gets a little nudge and reminder. Above all, it clearly highlights the action you want them to take.

The calls to action I mentioned are very different from one another, and they trigger very different reactions in me. I want to create a great game. With advertising, I want to draw attention to it and build excitement. I want to spark interest, but I don’t want to tell anyone what to do. I’d like people to take action because they genuinely like my product. But it doesn’t feel good to ask a stranger for support.

It’s a good thing I’m already writing posts before the big advertising push, because calls to action are genuinely hard for me, and I need to learn how to do them. For example, I’ve gotten used to asking questions in my posts to invite people to participate. That actually feels completely fine and fitting, though it still takes some getting used to. It’s probably easier because I’m not really asking for support yet. It’s a request to do something, but it doesn’t require any real commitment — like signing up for a newsletter or spending money.

When I start asking for more support, everyone can still decide for themselves whether they want to give it or not. But I’m putting someone in a position where they might have to say no, and that can be uncomfortable for some people. That’s probably why it’s so hard for me. We’re used to saying no to ads by now, but you still don’t want to be perceived as “advertising.” You don’t want to come across like a big corporation trying to push products on people just to make money. But I do need support, and it is okay to ask for it. A project like this simply can’t be done alone in a meaningful way. And honestly, I’m not asking for anything huge — and thanks to anonymity, it shouldn’t be difficult for anyone to say no. I need to remind myself of that more often. Depending on your moral compass, advertising can be quite tricky.

18 - Paid Advertisment

18 - Paid Advertisment

Especially if you don’t want to sell only locally, you won’t be able to avoid paid advertising. Of course, organic advertising (spread through word of mouth and enthusiasm) is better in almost every way, but it will never reach the same audience. Why do I say “in almost every way”? Organic advertising takes an enormous amount of time. Paid advertising is also very inexpensive, especially when it points to a great product — that’s when it becomes truly efficient.

It’s also important to keep the right target group in mind. For example, you can place ads on BoardGameGeek, the largest platform for board games, or in other specialized forums. Or on various social media platforms.

For board games on Kickstarter, Facebook advertising actually seems to be the most efficient. At least, that’s what you read in board game design groups and blogs. The advantage here is mainly that you can define very precisely which target groups will see your ads. Apparently, you can also run very effective A/B tests. That means: I can show one version of the ad with slightly different wording to 100 people, and another version to a different group of 100 people. Based on their reactions, I can see which wording works better. This allows you to optimize your posts.

However, I’ve often read that ads on BoardGameGeek tend to work better for more complex games, and that otherwise the advertising there is relatively expensive.

You should be especially careful when it comes to pricing. It’s a tricky topic. Depending on the type of ad, you usually pay differently. Often it’s based on impressions — meaning how many people saw the ad. But just because an ad was shown 1,000 times doesn’t mean everyone is interested, or that they click for more information, or that everyone who clicks signs up for the newsletter, or that everyone who gets that far is actually willing to buy the game.

Photo by Andre Benz on Unsplash

So if I pay €1.70 per click on my ad, but only every tenth click leads to a purchase, that means I paid €17 in advertising for that customer. If my profit margin is €18, that customer is still a profit! Naturally, larger and more expensive games give you more room to work with. And more customers might allow me to produce a larger print run, which makes manufacturing cheaper.

There are also several positive effects of advertising that are difficult or even impossible to measure. Clicks that lead to your site bring you traffic, and you appear more often to other potential customers. People might share information about your game even if they don’t buy it themselves. And you can find fans who bring life to your pages or help you in other ways. It also generally helps when people have already seen or heard about a product before. Maybe I don’t click the first time I see an ad, but the next time I read something about the game, I might. Sure, there may be people who get annoyed by ads and therefore refuse to buy the product — but who knows whether they would have ever seen it, and then bought it, without the ad? So this point probably doesn’t weigh too heavily. As I said, these effects are very hard to measure, but they are mostly very positive side effects of advertising.

I haven’t run any paid ads for my game yet. I’ll report more once I have. These are primarily things I’ve found online or learned in marketing seminars and during my psychology studies. I’m sure some of you can add more precise insights. I — and certainly other readers — would really appreciate your comments!

Update 1: In the meantime, I have run ads, but I wasn’t able to track them properly. That makes it hard for me to judge how effective they were. There are trackers you need to install on the page your ad links to. Unfortunately, I didn’t have enough time to look into this properly.

Update 2: I unfortunately can’t say how effective Facebook advertising will still be in 2026. I know (though only from my personal circle) that hardly any of my friends use Facebook anymore since so many AI-generated posts started appearing there.

17 - Reviews and Previews

17 - Reviews und Previews

With the large number of new board games released every year, many board gamers look at reviews before making a purchase. This primarily includes reviews in magazines, board game blogs, podcasts, and above all video reviews on YouTube.

These are also excellent ways to reach players for Kickstarter campaigns. It is often recommended to start building relationships with reviewers as early as possible, since they frequently need some lead time to produce content—especially when it comes to YouTube videos. However, I have found that this approach is not always ideal when you are an unknown board game designer.

There are many board gamers who are working on a board game idea, but many of these ideas are never realized, or only after years. As someone who writes reviews myself, I can understand why you might not want to schedule time for someone from whom nothing may ever materialize. It therefore helps to already have something tangible to show, and depending on the scope of the game, it can take quite a while until you have something where the design and illustrations already look appealing. Initial contacts can also be made very effectively at conventions and, of course, when you are already part of the reviewer’s community.

Photo by Markus Winkler on Unsplash

In addition, it is important to research what kind of content is being produced. Does the channel focus on certain genres or mechanics that fit my game? Are previews shown from time to time—that is, games that are not yet available for purchase—or only games that are already on the market? Some creators also show games that are clearly not finished yet; others do previews as well, but only if the preview prototype already looks very polished.

It is also important to note that some reviewers or previewers charge money to produce their content. This is understandable, as there is often a great deal of work involved. However, there are also many who are happy to create content for free, as long as the game is interesting to them.

It is also worth considering providing reviews in different languages. On Kickstarter, you can usually assume that at least 60% of customers are English-speaking, so English-language reviews are definitely essential. Since I also plan to produce a German version, German should of course not be missing either. If additional languages can be included beyond that, it certainly won’t hurt—provided you can distribute the game well in those regions.

Do you also like to watch reviews? If so, which formats do you prefer, and which reviewers do you particularly enjoy? I’m curious to hear which ones you mention—there are so many, and you keep discovering new great channels all the time.

16 - Trade Shows and Conventions

16 - Messen und Conventions

Conventions and trade shows are excellent places to make valuable connections. These might include media contacts, publishers, manufacturers, logistics partners, or fans of your game—or of you as an author. Importantly, these connections can be made both as a visitor and as an exhibitor.

As a visitor, you can walk from booth to booth, but you’ll often miss many people—especially those without booths, like media contacts. Still, these interactions are incredibly valuable, and you can also get a good sense of what your own booth might look like next year.

Having a booth is expensive, especially considering how many people you actually reach. In terms of acquiring new customers, the investment rarely pays off—unless you’re also selling games directly at the booth. Beyond the booth rental itself, there are costs for decoration, travel, and possibly extra shipping for bulky decor or games, especially if you’re offering them by the pallet.

However, being an exhibitor makes it much easier for others to find you, and it’s also a great opportunity to showcase your work—something that’s often difficult as a visitor. Many reviewers and potential fans don’t have booths themselves, so they need to be able to find you.

Trade show contacts are extremely valuable because you’ve already made direct contact. You’ve met in person, and there’s no hesitation about reaching out again. Interested parties are not only likely to become customers—they might even become supporters by promoting your game or helping in other ways. After all, they now know the game designer personally and can get involved. The personal experience visitors have with you sticks with them for a long time. I’m convinced there’s no form of advertising with a longer-lasting effect.

Sure, people remember you when they see a picture of you or your game. But that doesn’t mean they’ll think of it at the right moment. That’s why it’s so important to point them toward your newsletter and social media. That way, they can support you when it’s time to say “Kickstarter is live!” or when there’s an interesting post to share and comment on.

You might even be able to hand out review copies directly at the show, saving on shipping costs and delivery time. That’s not to be underestimated—you often don’t have many review copies, and they need to reach and be played by as many people as possible.

During COVID, things got a lot trickier. Digital conventions became the norm. As an exhibitor, I’m still not particularly enthusiastic about them. Sometimes the “booth fees” are still quite high, and there’s a lot of extra work involved. Usually, you need to set up a website that looks professional and appealing. And unless you offer a livestream where you can interact with visitors, the whole thing lacks a personal touch. If you want the livestream to look polished, that’s a huge amount of work!

The advantage of digital conventions is their accessibility—especially since they’re usually free for visitors. So you can expect decent traffic. But that doesn’t mean visitors will “pass by” your booth like they would at a physical event. It’s a very different experience. For example, when I exhibit at Spiel in Essen, I can speak to every visitor in either German or English. Online, I have to choose just one language for the livestream. And it’s a different dynamic when someone isn’t standing in front of you. Viewers are completely anonymous—you can ask for questions and comments, but interaction has to be initiated from their side.

Also, there’s no real reason why these contacts couldn’t just be made online. Anyone attending a digital convention can find your content online anyway. Even selling at a booth doesn’t feel any different than selling through a webshop.

From others who participated digitally at Spiel, I mostly heard that it felt like a flop—expensive, a lot of effort, and not many “visitors.

After Attending Several Conventions:

Conventions vary widely—some focus entirely on board games, others on gaming in general. Gaming conventions are often split between digital and analog formats. You can see this in the attendees: a large portion is only interested in the digital side. So the number of truly interested visitors is much lower than the total attendance.

Conventions are always a big effort, and you have to weigh whether the cost is worth it. The Spiel in Essen, thanks to its size and visitor numbers, is reasonably priced. But as an exhibitor, including travel and setup/teardown, you’ll need about a week.

Still, the experience as an exhibitor at Spiel is always fantastic, and it pains me every time I can’t have a booth. I love being there every year. The connections are amazing—whether it’s fans with great ideas or other designers, publishers, and manufacturers you can learn a lot from.

What kind of experiences have you had at board game conventions, whether physical or digital? Opinions surely vary—I’m curious to hear yours!

15 – How Do You Become Part of a Community? Social Media (Part 2)

15 - Wie gründet man eine eigene Community? Social Media (2)

There are several social media platforms that allow you to create your own communities. Generally speaking, there are three key points to keep in mind:

The content should be interesting to the community—otherwise, members have no incentive to stay.

Content needs to be posted regularly, and inquiries should be answered promptly. If the channel is active, the chances of having active members increase significantly. Reach—meaning who sees your posts—is heavily influenced by activity on many platforms.

The content should match the platform. Different platforms clearly target specific types of information.

Based on my personal experience, certain channels work particularly well when it comes to board games and Kickstarter. It’s also important to consider whether you want to build a community around a specific game/publisher or a broader topic. The effort required can vary greatly.

Facebook:

Best suited for discussions around specific topics. A large portion of the content is created by active members.

A Facebook page is mainly used to post information about a product or company. Posts here are mostly written by the owner, and followers are less involved.

Facebook Group: Facebook communities primarily operate through groups. If you want people to exchange ideas about a game, a Facebook group is a good idea. It’s important to post questions and spark discussions. It’s also recommended to allow members to post in the group, but keep an eye on things to ensure comments and posts don’t get out of hand. Facebook offers a wide range of excellent groups for topic-specific exchanges, and members tend to be very active.

Instagram:

Ideal for posting images. Especially for board games, illustrations create a strong mood and atmosphere. Instagram favors frequent posting of images and stories (short posts that disappear after a while) to increase visibility. It’s a great platform for getting feedback on visuals. Don’t forget to add text to your images—questions tend to get more responses! Short videos have also become very popular and significantly increase your chances of being recommended to other users. Instagram also expects a lot of interaction beyond your own posts, such as liking and commenting on others’ content.

Blog:

A blog allows readers to get to know the author better. It’s a great way to share opinions, interests, and expertise, and to connect with like-minded individuals. As with all other channels, it’s important to engage with the community—so be sure to ask questions! Encourage readers to leave comments you can respond to. This boosts the channel’s relevance and motivates the writer. 😉

YouTube:

Like a blog, YouTube lets you share opinions, interests, and expertise. If the focus is solely on a board game or Kickstarter, a “making-of” video could be an option. However, keep in mind that a lot of material is needed to maintain community interest. If you’re creating a general board game channel, remember that producing videos is time-consuming—especially if you want them to look professional. You’ll need equipment and plenty of time.

Podcasts:

I don’t have much experience with podcasts yet, but I think they’re similar to blogs or YouTube. The main challenge is making episodes engaging through conversations with guests. So it’s not just a regular time commitment for you, but also for others. That said, board game podcasts are quite popular.

Twitter:

Seems to be less relevant for board games, since only short text posts are possible. Board games often require more explanation. While you can post images here too, Instagram offers much better options for that.

Foren:

BoardGameGeek and Reddit are examples of massive platforms. It’s definitely worth being an active part of these communities, as you can find people interested in your own community there. BoardGameGeek feels very open and helpful, though the platform is extensive and takes time to navigate. Reddit is a bit different—you should familiarize yourself with its social norms before diving in. The community is powerful, but not easily accessible.

There’s a lot to say on this topic. If you have questions or suggestions, feel free to share! Have you built your own community? How did it go? I’m really looking forward to your comments. There will definitely be more posts on this subject in the future.