22 - Illustrations and Production (Bleed and Margin)

22 - Illustrations and Production (Bleed and Margin)

When you start planning illustrations for your game, it’s a good idea to familiarize yourself with production standards. Doing so can save you a lot of work later on.

Panda Game Manufacturing even provides a Design Guide Book for this, which is incredibly helpful. In this post, I’ll talk about bleed and margin (trim area and safety area), and in the next one I’ll cover printing plates. However, design templates aren’t the same for every manufacturer.

You can assume that most manufacturers work with a bleed and margin of 3 mm. But what does that mean?

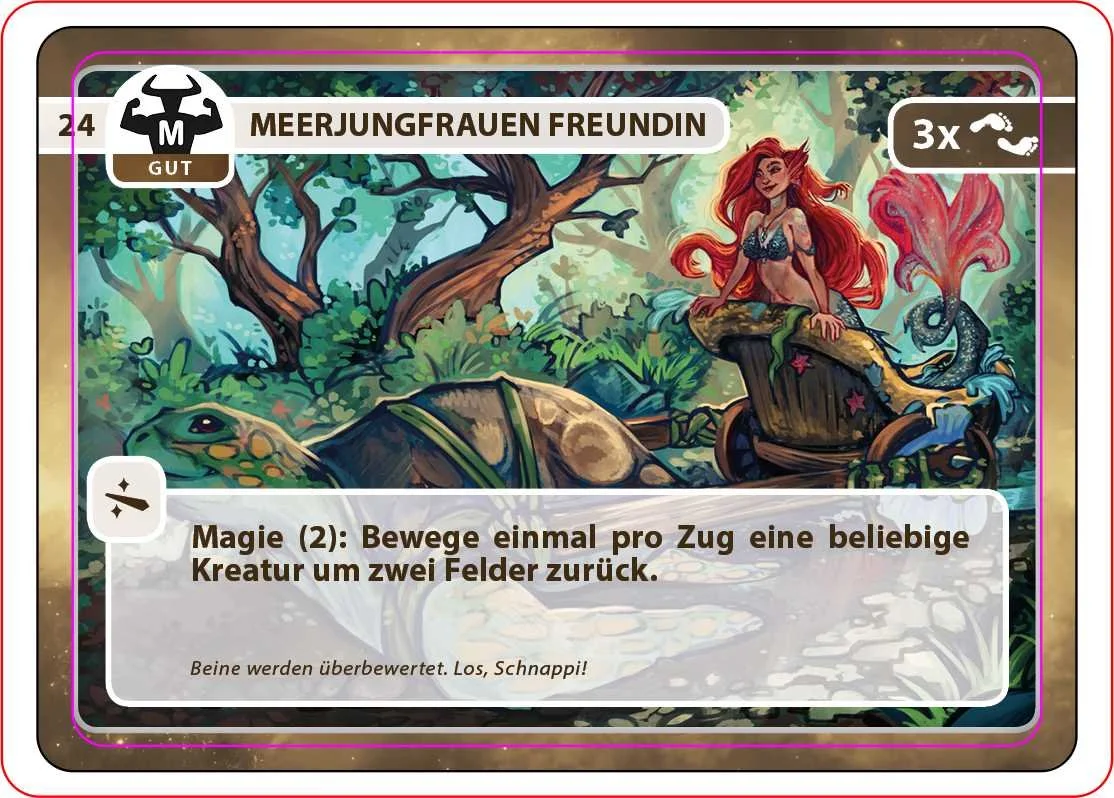

In this image of our card, I’ve drawn a red line. It represents the bleed. The purple line marks the margin. The black line shows the actual size of the card and the intended visible area.

The card is printed and then die‑cut. But the machine has a certain tolerance — small deviations that simply happen. The cut won’t always be exactly where the black line is; it might be slightly higher or lower, a bit to the left or right. Normally, these deviations don’t reach the full 3 mm. If they did, customers would probably complain.

In this case, the colored border of the card needs to extend all the way to the red line (the bleed). Otherwise, if the cut shifts, you’d end up with a white edge on one or two sides. Even a tiny white edge would be noticeable and unpleasant. But if the cut shifts slightly to the left, that also means the right side will be cut deeper into the black area. That’s why you need to respect the margin (purple). The area between the black and purple lines shouldn’t contain any important information. In our example, the card number 24 would be cut off if the cut were actually 3 mm too far to the right.

Both bleed and margin are factors that must be considered for any printed and cut object. So especially with cards, you need to choose a design where bleed and margin won’t cause problems. The same applies to die‑cut cardboard components. With certain shapes, it’s not easy to maintain proper bleed and margin.

If I’ve forgotten something important in my explanation, please leave me a comment. And if you have any questions, feel free to ask — I’m sure you’re not the only one who would benefit from the answer.

21 - Can I Do All of This on My Own?

21 - Can I Do All of This on My Own?

By now, I’ve spent over 1,800 hours working on the game and the Kickstarter. For various reasons, I’m currently treating it as a full‑time job, and I don’t have a side job. Of course, that comes with some uncertainties, but I won’t go into those in this entry. In theory, you can do a lot of things on your own — but just because you can doesn’t mean it’s a good idea.

Designing a game together with someone else is certainly great and motivating. But it only works well if both people bring enough commitment and time. As people get older and start families, it often becomes harder to find someone for a project like this. Testing, on the other hand, is a bit easier — people often have time for that, and testing is incredibly important for the development process. That support is unbelievably valuable.

You can teach yourself many of the things you need. But some skills require so much practice that it really makes sense to get help. As I mentioned in an earlier post, illustration and graphic design are areas where I personally need support. Writing and crafting text also takes practice. If that’s not going so well yet, you need someone who can look over your work. A good working relationship with these collaborators is worth its weight in gold — especially when you’re working on the project alone, and even more so during the COVID lockdowns.

We work together regularly — at the moment, of course, digitally (during COVID). We use Discord for that. Even if we’re each working on our own tasks, seeing and hearing each other via webcam, exchanging thoughts now and then, and getting immediate feedback and opinions on certain things is fantastic. It’s incredibly motivating and inspiring.

If you manage to work on something alone for so long without occasionally falling into a motivation slump, running out of energy, or having your creativity refuse to cooperate — hats off to you. A great team helps immensely.

I hope you’re doing well during the lockdown and that you still have colleagues you can rely on. What helps you when things get particularly tough?

Update: This post was written during the COVID lockdown.

20 - The Prototype and the Rulebook

20 - The Prototype and the Rulebook

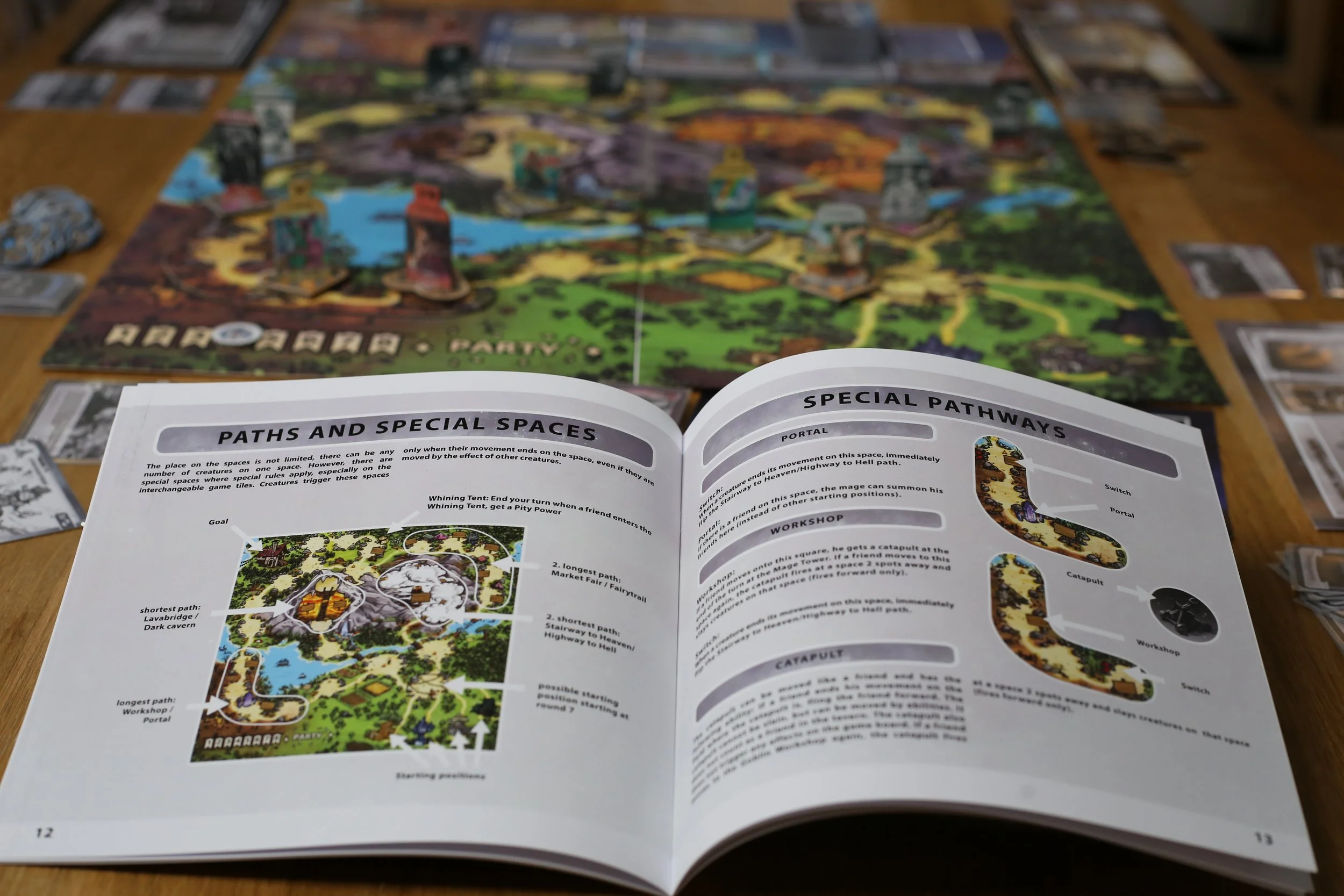

Even though the rulebook is usually ignored after the first few games, it is an extremely important part of any game.

Unfortunately, it’s also a part that requires a lot of work — especially if you don’t particularly enjoy writing … and if you plan to publish the game in two languages.

The earlier you write down a meaningful rulebook, the better. On the one hand, the game can then be tested without a personal explanation. On the other hand, it’s not only the game that needs testing, but also the rules themselves. If the rules are interpreted incorrectly, the game will be played incorrectly, and the playtest becomes only partially useful.

A written rulebook is often much longer than the usual verbal explanation of the rules. The quick clarifications you can answer with a simple “yes” or “no” during an explanation also need to be addressed in the written version.

There are several helpful tips online about how to write board game rulebooks, and it certainly doesn’t hurt to look through them.

It’s definitely useful to study rulebooks from games where you personally feel the rules are well explained. But going through the rules of very well‑known games isn’t a bad idea either. You’ll notice a common structure that board gamers are already familiar with.

It’s also helpful to think about the structure of your rulebook — in what order should the game be explained? Sometimes it’s beneficial to repeat certain rules. For example, it doesn’t hurt to mention the game’s objective early on, but it’s also useful to repeat it again during the final scoring section at the end of the rules.

After the first few plays, the rulebook is mostly used for reference. Can players find information easily? Are all questions answered?

These are questions only testers can answer for me. Since all of this is not easy, it’s also difficult to reach a point where you can say: “Okay, this version of the rules is good/pretty enough to share.” Too many errors mean the rules aren’t very helpful and can frustrate testers. But without testers, you won’t discover many mistakes or opportunities for improvement. And when do you hand everything over to an editor? There will be many versions of the rulebook.

The rulebook for Magical Friends has already gone through many revisions, but now you can finally view it online. On the landing page, you can download the PDF if you like. I’m very happy about any feedback — but I’ll warn you in advance: there will probably be many more adjustments before it goes to an editor, and of course many images will still be replaced.

Are you also working on a rulebook? What problems have you encountered? If you take a look at the rules, your feedback will definitely help me improve them. Every tip is appreciated!

Update: Now that the game has been published, the rulebook is definitely the number one thing I want to improve for a second edition. ;-)

19 - Call to Action

19 - Call to Action

One of the most important parts of advertising is the “call to action” — the invitation to do something. At the same time, it’s also one of the most difficult parts for me personally. Ads that include a call to action are much more effective than those without. If you look up “call to action,” you’ll quickly find plenty of articles on the topic.

Such a call might be asking the reader or viewer to subscribe to a newsletter, like a post, follow a page, buy a product, or simply join a discussion. It’s an invitation to participate or a request for support. Someone who might not have thought about supporting a product or who doesn’t yet feel part of the community gets a little nudge and reminder. Above all, it clearly highlights the action you want them to take.

The calls to action I mentioned are very different from one another, and they trigger very different reactions in me. I want to create a great game. With advertising, I want to draw attention to it and build excitement. I want to spark interest, but I don’t want to tell anyone what to do. I’d like people to take action because they genuinely like my product. But it doesn’t feel good to ask a stranger for support.

It’s a good thing I’m already writing posts before the big advertising push, because calls to action are genuinely hard for me, and I need to learn how to do them. For example, I’ve gotten used to asking questions in my posts to invite people to participate. That actually feels completely fine and fitting, though it still takes some getting used to. It’s probably easier because I’m not really asking for support yet. It’s a request to do something, but it doesn’t require any real commitment — like signing up for a newsletter or spending money.

When I start asking for more support, everyone can still decide for themselves whether they want to give it or not. But I’m putting someone in a position where they might have to say no, and that can be uncomfortable for some people. That’s probably why it’s so hard for me. We’re used to saying no to ads by now, but you still don’t want to be perceived as “advertising.” You don’t want to come across like a big corporation trying to push products on people just to make money. But I do need support, and it is okay to ask for it. A project like this simply can’t be done alone in a meaningful way. And honestly, I’m not asking for anything huge — and thanks to anonymity, it shouldn’t be difficult for anyone to say no. I need to remind myself of that more often. Depending on your moral compass, advertising can be quite tricky.

18 - Paid Advertisment

18 - Paid Advertisment

Especially if you don’t want to sell only locally, you won’t be able to avoid paid advertising. Of course, organic advertising (spread through word of mouth and enthusiasm) is better in almost every way, but it will never reach the same audience. Why do I say “in almost every way”? Organic advertising takes an enormous amount of time. Paid advertising is also very inexpensive, especially when it points to a great product — that’s when it becomes truly efficient.

It’s also important to keep the right target group in mind. For example, you can place ads on BoardGameGeek, the largest platform for board games, or in other specialized forums. Or on various social media platforms.

For board games on Kickstarter, Facebook advertising actually seems to be the most efficient. At least, that’s what you read in board game design groups and blogs. The advantage here is mainly that you can define very precisely which target groups will see your ads. Apparently, you can also run very effective A/B tests. That means: I can show one version of the ad with slightly different wording to 100 people, and another version to a different group of 100 people. Based on their reactions, I can see which wording works better. This allows you to optimize your posts.

However, I’ve often read that ads on BoardGameGeek tend to work better for more complex games, and that otherwise the advertising there is relatively expensive.

You should be especially careful when it comes to pricing. It’s a tricky topic. Depending on the type of ad, you usually pay differently. Often it’s based on impressions — meaning how many people saw the ad. But just because an ad was shown 1,000 times doesn’t mean everyone is interested, or that they click for more information, or that everyone who clicks signs up for the newsletter, or that everyone who gets that far is actually willing to buy the game.

Photo by Andre Benz on Unsplash

So if I pay €1.70 per click on my ad, but only every tenth click leads to a purchase, that means I paid €17 in advertising for that customer. If my profit margin is €18, that customer is still a profit! Naturally, larger and more expensive games give you more room to work with. And more customers might allow me to produce a larger print run, which makes manufacturing cheaper.

There are also several positive effects of advertising that are difficult or even impossible to measure. Clicks that lead to your site bring you traffic, and you appear more often to other potential customers. People might share information about your game even if they don’t buy it themselves. And you can find fans who bring life to your pages or help you in other ways. It also generally helps when people have already seen or heard about a product before. Maybe I don’t click the first time I see an ad, but the next time I read something about the game, I might. Sure, there may be people who get annoyed by ads and therefore refuse to buy the product — but who knows whether they would have ever seen it, and then bought it, without the ad? So this point probably doesn’t weigh too heavily. As I said, these effects are very hard to measure, but they are mostly very positive side effects of advertising.

I haven’t run any paid ads for my game yet. I’ll report more once I have. These are primarily things I’ve found online or learned in marketing seminars and during my psychology studies. I’m sure some of you can add more precise insights. I — and certainly other readers — would really appreciate your comments!

Update 1: In the meantime, I have run ads, but I wasn’t able to track them properly. That makes it hard for me to judge how effective they were. There are trackers you need to install on the page your ad links to. Unfortunately, I didn’t have enough time to look into this properly.

Update 2: I unfortunately can’t say how effective Facebook advertising will still be in 2026. I know (though only from my personal circle) that hardly any of my friends use Facebook anymore since so many AI-generated posts started appearing there.

17 - Reviews and Previews

17 - Reviews und Previews

With the large number of new board games released every year, many board gamers look at reviews before making a purchase. This primarily includes reviews in magazines, board game blogs, podcasts, and above all video reviews on YouTube.

These are also excellent ways to reach players for Kickstarter campaigns. It is often recommended to start building relationships with reviewers as early as possible, since they frequently need some lead time to produce content—especially when it comes to YouTube videos. However, I have found that this approach is not always ideal when you are an unknown board game designer.

There are many board gamers who are working on a board game idea, but many of these ideas are never realized, or only after years. As someone who writes reviews myself, I can understand why you might not want to schedule time for someone from whom nothing may ever materialize. It therefore helps to already have something tangible to show, and depending on the scope of the game, it can take quite a while until you have something where the design and illustrations already look appealing. Initial contacts can also be made very effectively at conventions and, of course, when you are already part of the reviewer’s community.

Photo by Markus Winkler on Unsplash

In addition, it is important to research what kind of content is being produced. Does the channel focus on certain genres or mechanics that fit my game? Are previews shown from time to time—that is, games that are not yet available for purchase—or only games that are already on the market? Some creators also show games that are clearly not finished yet; others do previews as well, but only if the preview prototype already looks very polished.

It is also important to note that some reviewers or previewers charge money to produce their content. This is understandable, as there is often a great deal of work involved. However, there are also many who are happy to create content for free, as long as the game is interesting to them.

It is also worth considering providing reviews in different languages. On Kickstarter, you can usually assume that at least 60% of customers are English-speaking, so English-language reviews are definitely essential. Since I also plan to produce a German version, German should of course not be missing either. If additional languages can be included beyond that, it certainly won’t hurt—provided you can distribute the game well in those regions.

Do you also like to watch reviews? If so, which formats do you prefer, and which reviewers do you particularly enjoy? I’m curious to hear which ones you mention—there are so many, and you keep discovering new great channels all the time.

16 - Trade Shows and Conventions

16 - Messen und Conventions

Conventions and trade shows are excellent places to make valuable connections. These might include media contacts, publishers, manufacturers, logistics partners, or fans of your game—or of you as an author. Importantly, these connections can be made both as a visitor and as an exhibitor.

As a visitor, you can walk from booth to booth, but you’ll often miss many people—especially those without booths, like media contacts. Still, these interactions are incredibly valuable, and you can also get a good sense of what your own booth might look like next year.

Having a booth is expensive, especially considering how many people you actually reach. In terms of acquiring new customers, the investment rarely pays off—unless you’re also selling games directly at the booth. Beyond the booth rental itself, there are costs for decoration, travel, and possibly extra shipping for bulky decor or games, especially if you’re offering them by the pallet.

However, being an exhibitor makes it much easier for others to find you, and it’s also a great opportunity to showcase your work—something that’s often difficult as a visitor. Many reviewers and potential fans don’t have booths themselves, so they need to be able to find you.

Trade show contacts are extremely valuable because you’ve already made direct contact. You’ve met in person, and there’s no hesitation about reaching out again. Interested parties are not only likely to become customers—they might even become supporters by promoting your game or helping in other ways. After all, they now know the game designer personally and can get involved. The personal experience visitors have with you sticks with them for a long time. I’m convinced there’s no form of advertising with a longer-lasting effect.

Sure, people remember you when they see a picture of you or your game. But that doesn’t mean they’ll think of it at the right moment. That’s why it’s so important to point them toward your newsletter and social media. That way, they can support you when it’s time to say “Kickstarter is live!” or when there’s an interesting post to share and comment on.

You might even be able to hand out review copies directly at the show, saving on shipping costs and delivery time. That’s not to be underestimated—you often don’t have many review copies, and they need to reach and be played by as many people as possible.

During COVID, things got a lot trickier. Digital conventions became the norm. As an exhibitor, I’m still not particularly enthusiastic about them. Sometimes the “booth fees” are still quite high, and there’s a lot of extra work involved. Usually, you need to set up a website that looks professional and appealing. And unless you offer a livestream where you can interact with visitors, the whole thing lacks a personal touch. If you want the livestream to look polished, that’s a huge amount of work!

The advantage of digital conventions is their accessibility—especially since they’re usually free for visitors. So you can expect decent traffic. But that doesn’t mean visitors will “pass by” your booth like they would at a physical event. It’s a very different experience. For example, when I exhibit at Spiel in Essen, I can speak to every visitor in either German or English. Online, I have to choose just one language for the livestream. And it’s a different dynamic when someone isn’t standing in front of you. Viewers are completely anonymous—you can ask for questions and comments, but interaction has to be initiated from their side.

Also, there’s no real reason why these contacts couldn’t just be made online. Anyone attending a digital convention can find your content online anyway. Even selling at a booth doesn’t feel any different than selling through a webshop.

From others who participated digitally at Spiel, I mostly heard that it felt like a flop—expensive, a lot of effort, and not many “visitors.

After Attending Several Conventions:

Conventions vary widely—some focus entirely on board games, others on gaming in general. Gaming conventions are often split between digital and analog formats. You can see this in the attendees: a large portion is only interested in the digital side. So the number of truly interested visitors is much lower than the total attendance.

Conventions are always a big effort, and you have to weigh whether the cost is worth it. The Spiel in Essen, thanks to its size and visitor numbers, is reasonably priced. But as an exhibitor, including travel and setup/teardown, you’ll need about a week.

Still, the experience as an exhibitor at Spiel is always fantastic, and it pains me every time I can’t have a booth. I love being there every year. The connections are amazing—whether it’s fans with great ideas or other designers, publishers, and manufacturers you can learn a lot from.

What kind of experiences have you had at board game conventions, whether physical or digital? Opinions surely vary—I’m curious to hear yours!

15 – How Do You Become Part of a Community? Social Media (Part 2)

15 - Wie gründet man eine eigene Community? Social Media (2)

There are several social media platforms that allow you to create your own communities. Generally speaking, there are three key points to keep in mind:

The content should be interesting to the community—otherwise, members have no incentive to stay.

Content needs to be posted regularly, and inquiries should be answered promptly. If the channel is active, the chances of having active members increase significantly. Reach—meaning who sees your posts—is heavily influenced by activity on many platforms.

The content should match the platform. Different platforms clearly target specific types of information.

Based on my personal experience, certain channels work particularly well when it comes to board games and Kickstarter. It’s also important to consider whether you want to build a community around a specific game/publisher or a broader topic. The effort required can vary greatly.

Facebook:

Best suited for discussions around specific topics. A large portion of the content is created by active members.

A Facebook page is mainly used to post information about a product or company. Posts here are mostly written by the owner, and followers are less involved.

Facebook Group: Facebook communities primarily operate through groups. If you want people to exchange ideas about a game, a Facebook group is a good idea. It’s important to post questions and spark discussions. It’s also recommended to allow members to post in the group, but keep an eye on things to ensure comments and posts don’t get out of hand. Facebook offers a wide range of excellent groups for topic-specific exchanges, and members tend to be very active.

Instagram:

Ideal for posting images. Especially for board games, illustrations create a strong mood and atmosphere. Instagram favors frequent posting of images and stories (short posts that disappear after a while) to increase visibility. It’s a great platform for getting feedback on visuals. Don’t forget to add text to your images—questions tend to get more responses! Short videos have also become very popular and significantly increase your chances of being recommended to other users. Instagram also expects a lot of interaction beyond your own posts, such as liking and commenting on others’ content.

Blog:

A blog allows readers to get to know the author better. It’s a great way to share opinions, interests, and expertise, and to connect with like-minded individuals. As with all other channels, it’s important to engage with the community—so be sure to ask questions! Encourage readers to leave comments you can respond to. This boosts the channel’s relevance and motivates the writer. 😉

YouTube:

Like a blog, YouTube lets you share opinions, interests, and expertise. If the focus is solely on a board game or Kickstarter, a “making-of” video could be an option. However, keep in mind that a lot of material is needed to maintain community interest. If you’re creating a general board game channel, remember that producing videos is time-consuming—especially if you want them to look professional. You’ll need equipment and plenty of time.

Podcasts:

I don’t have much experience with podcasts yet, but I think they’re similar to blogs or YouTube. The main challenge is making episodes engaging through conversations with guests. So it’s not just a regular time commitment for you, but also for others. That said, board game podcasts are quite popular.

Twitter:

Seems to be less relevant for board games, since only short text posts are possible. Board games often require more explanation. While you can post images here too, Instagram offers much better options for that.

Foren:

BoardGameGeek and Reddit are examples of massive platforms. It’s definitely worth being an active part of these communities, as you can find people interested in your own community there. BoardGameGeek feels very open and helpful, though the platform is extensive and takes time to navigate. Reddit is a bit different—you should familiarize yourself with its social norms before diving in. The community is powerful, but not easily accessible.

There’s a lot to say on this topic. If you have questions or suggestions, feel free to share! Have you built your own community? How did it go? I’m really looking forward to your comments. There will definitely be more posts on this subject in the future.

14 – How Do You Become Part of a Community? Social Media (Part 1)

14 – How Do You Become Part of a Community? Social Media (Part 1)

On social media platforms—whether it’s Facebook or online forums—it’s easy to follow a community. But does that mean you’re truly part of that group?

Even if you read every post and know exactly who writes the most interesting content, which inside jokes are common, and what social norms have developed there—you might feel like part of the group. But does the group actually recognize you as a member?

Unlike real life, just being there goes unnoticed on social media. You recognize others because they contribute—by posting or commenting. But no one notices if you’re just reading or occasionally liking something. You only become visible—and accepted—when you start contributing and interacting. That’s when the community starts to see you as one of their own.

Photo by George Pagan III on Unsplash

I personally consider myself very much a part of the board game community: I’ve introduced many people to games in Salzburg and organized events. I design a game for players and have poured time and resources into the project. That certainly makes me a board gamer—but unless I actually participate in specific board game communities, people there won’t know me.

This can especially be a problem when it comes to promotion. In many groups, it’s frowned upon if your first post is a game announcement. Sure, you’re sharing something the group might genuinely enjoy—something they wouldn’t have discovered otherwise. But to them, you’re still a stranger promoting a product.

You don’t have to be part of every community. But it’s worth becoming active in key groups, especially the larger ones where conversations happen. Just be aware—it takes time and effort. Don’t expect to be well-known after just a few weeks. Post meaningful content. Engage in conversations. Offer the community something of value. That’s what builds interest in you—and eventually, in your game too.

On top of that, regular activity boosts your visibility. Many social media platforms reduce your reach if there’s little interaction. But that’s a topic for another post.

If you’re part of a board game community yourself, I’d be thrilled to receive an invite. I’d love to introduce myself and my game, and I’d be happy to answer your questions—if I’m welcome and invited, of course. I’d truly appreciate it.

13 – Why Are Newsletters So Important for Crowdfunding Projects?

13 - Warum sind Newsletter so wichtig bei Crowdfunding Projekten?

When I looked into marketing for crowdfunding campaigns—at least in the board game world—the most common question I heard was: “How big is your email list? You need newsletter subscribers.”

There are several reasons for this. I’ve already mentioned that it’s good to start marketing early. But the earlier I begin, the longer interested people have to wait for the game. A newsletter gives me a way to stay in touch with very little interaction. You only have to sign up once, and from then on, you’ll stay updated with almost no effort. You can read the email and catch up when you have time—unlike social media posts, which quickly disappear into the feed.

That said, it’s really important that the newsletter is well-crafted. I want my readers to benefit from it—not feel annoyed. That starts with the subject line: it shouldn’t feel like spam. After all, the recipient signed up and showed interest in the game. So it should be clear that it’s about the game, and it shouldn’t sound like a sales pitch.

I now divide my newsletters into 4 to 5 short sections on different topics. They’re not long and are usually illustrated with images. I make sure the newsletter is concise yet informative—so readers learn something new or get a glimpse of the game. I vary the content too:

Information about the game mechanics for those who just want to understand how it plays

Insights about the team to build trust with the creator

Artwork to capture the game’s atmosphere

What’s coming next—so readers have something to look forward to

Occasional updates on special events

With this mix, I hope to cover at least two areas of interest for each subscriber, keeping the excitement alive. I also ask questions to spark conversations with my readers—these interactions are incredibly valuable. Even later on, they help gather key feedback or rally support for your Kickstarter.

To grow your email list, mention the newsletter subscription at every opportunity. Ask people if they’d like to be added. Be transparent about how their email will be used. And definitely set up a landing page—a simple site focused on getting people to subscribe. That’s what I did for Magical Friends.

I used Mailchimp.com to send my newsletters. I'm happy with how easy it was to create and distribute them, and the site also offers great analytics tools. It even lets you create a landing page—though I’m not fully sold on those options yet. The Landing Page is still there, but now I got the Publishers site for new things to come.

Overall, I found marketing pretty challenging. I wasn’t able to grow my subscriber list as much as I’d hoped. It really takes a lot of time and persistence!

12 - How to Get Noticed

To sell a game in a meaningful quantity, friends and acquaintances alone aren’t enough—you also need to attract strangers. That’s not possible without advertising.

In this post, I’ll share some experiences from others in the industry, as well as my own journey. There are several major topics I’ll likely cover in separate posts:

Social Media

Newsletters

Reviewers

Trade Show Appearances

Paid Advertising

But before diving into those points: When should you start advertising?

The general consensus is pretty clear—the earlier, the better. Naturally, you might wonder whether people will lose interest in the game over time. That’s true, which is why it’s crucial to keep them regularly (!) engaged with interesting updates. While some people will inevitably drop off, others will join in—and especially those who stick with your game all the way to Kickstarter are likely your most valuable fans. Those fans not only tend to support your game on Kickstarter but also often contribute to spreading the word ahead of time.

That said, there's a lot to keep in mind. Once you start telling people about your game, they should also have a way to follow you. If you don’t have a social media channel, website, or newsletter set up, the information you share will quickly be forgotten. Even worse, someone who’s genuinely excited about your project won’t be able to help spread the word.

Zeigt euch!

If you decide to launch a promotional campaign, be prepared—it marks the beginning of a larger, ongoing effort. You’ll only be able to sustain a certain level of excitement if you provide regular updates. That also means preparing enough interesting content for the weeks ahead. There's no turning back from here.

For the initial promotional effort, a Landingpage is highly recommended. It's a simple website that gives a brief overview of the game and, most importantly, offers visitors the chance to sign up for a newsletter.

More on that in the next post.

Have you had any experience with this topic? What’s your take on it? How long can you stay excited about a product? What do you enjoy supporting? Leave us a comment—we’d love to hear from you!

11 - Digital Testing

Not only during a pandemic is it advantageous to have a prototype available in digital form. Sending out multiple physical prototypes is laborious and time-consuming.

One of the first prototypes for Tabletop Simulator looked like this and was uploaded to the Steam Workshop. You'll now find a current version there, which anyone with Tabletop Simulator can play.

Digitally, a game like this can be updated much faster than a physical version. Even creating it is significantly easier than you might expect—especially card games, which are very easy to import. Tabletop Simulator offers a wide range of components, to which you simply assign an image. Some components are a bit more complex. Magical Friends, for instance, features a lot of creature standees. Making these enjoyable to use required a lot of consideration in the physical version. In Tabletop Simulator, there are containers and scripts for this. With scripts, you can solve many problems and even simplify things compared to a physical prototype. You just need to read up a bit or get some help (but the effort isn't too great).

However, Tabletop Simulator has one drawback: it's not free. This paywall unfortunately discourages many testers. Still, it's already used by a huge number of players, so you do end up with a large pool of potential testers.

There are also free platforms like Tabletopia. However, their features are very limited, and it's hard to include more complex components since there's no scripting option. I definitely plan to take a closer look at Tabletopia in the future. It’s evolving quite a bit.

One feature of Tabletop Simulator I’d like to highlight: you can include a tablet as a component, which allows you to use a browser directly within the game. That way, I can launch a website by default through which I can communicate with testers—without needing to change the game version.

Leave us a comment about what you think of this idea and about Tabletop Simulator in general. Of course, we’d also love it if you try out our game and leave us feedback.

What has your experience been like with tasks like these? Do you work in this field? I'm looking forward to your comments!

10 - How to Avoid Unnecessary Effort in the First Prototype (Part 3)

10 - How to Avoid Unnecessary Effort in the First Prototype (Part 3) (Teil 3)

In the third part about prototypes, we focus on testers:

Everywhere you read that a prototype should be inexpensive. It should be quickly discardable if it doesn’t work. It shouldn’t be too complex to modify. You will constantly be swapping and improving things. Additionally, mechanics should be added gradually. Furthermore, you don’t want to torment your testers, so it would be good if the game already functions reasonably well when you invite them.

If you want your testers to look at a game more than once, it helps if the game is already somewhat functional and has fun elements built in. That’s why it’s beneficial to try it out a few times beforehand with an especially enthusiastic friend. However, keep in mind that while a two-player game is easy to test with just two people, games designed for larger groups can be difficult to test with only two players.

For your board game, you will need many test rounds. Since you will typically need multiple players, this means you will also need a sufficient number of testers. That’s why it’s important to keep your testers engaged so they want to play multiple versions. You’ll have a few friends who really enjoy your game and will want to test different versions. However, board game preferences vary widely—not every player enjoys every type of mechanic or genre. This doesn’t mean your friends won’t want to help, but rotating testers and implementing improvements between sessions can ensure they see progress.

The duration of the game also affects test motivation. A game that can be completed in under an hour is much easier to bring to the table than a longer one. Additionally, frustration with unfinished mechanics is less severe in a shorter game than one that lasts two to three hours. If a longer game isn’t going well, it’s often better to end the session early. The feedback gathered will usually be enough to identify key issues.

It’s particularly important to test the game with strangers and/or blind testing (without assistance). Players should be able to complete a game based solely on the instructions, with no external help. However, before exposing the game to blind or public testing, the prototype should have already gone through multiple test rounds and reached a certain level of quality. While these settings can provide highly valuable feedback, they can also cause significant frustration.

For online prototype testing—where it’s easier to find remote testers—platforms like Tabletop Simulator or Tabletopia are useful.

My game is available on Tabletop Simulator in both German and English. If you’d like to try Magical Friends, you just need friends with Tabletop Simulator and can access it directly via the Steam Workshop: Steam Workshop Link. When launching the game, you’ll be notified that a link is being opened, through which a feedback form can be completed.

This is a very early form of the tabletop simulator version, now it almost looks like the real game.

I’d be happy about feedback, please write in the comments.

9 - How to Prevent Unnecessary Effort in the First Prototype (Part 2)

9 - How to Prevent Unnecessary Effort in the First Prototype (Part 2)

Heute geht es dort weiter, wo ich zuletzt aufgehört habe:

Überall liest man, dass ein Prototyp billig sein soll. So ein Prototyp soll schnell verwerfbar sein, falls er nicht funktioniert. Er soll nicht aufwendig sein, wenn man etwas verändern möchte. Man wird ständig Dinge austauschen und verbessern. Außerdem soll man Mechaniken nach und nach hinzufügen. Weiters möchte man seine Tester nicht quälen, es wäre also gut, wenn das Spiel schon einigermaßen funktioniert, wenn man Tester einlädt.

Zum Thema „Mechaniken nur nach und nach hinzuzufügen“ kann man einiges sagen. Generell ist es immer leichter, ein Spiel nach und nach komplexer zu gestalten und einen Kniff hier oder da hinzuzufügen, es aber an Stellen simpler zu machen, ist deutlich schwieriger. Wenn ein Spiel leicht zu lernen, aber schwer zu meistern ist, hat man auf jeden Fall etwas gut gemacht. So etwas anzustreben, ist nie verkehrt. Nachträglich etwas zu vereinfachen, bedeutet aber oft, dass man etwas verliert, wofür eine bestimmte Regel eingeführt wurde. Meistens taucht dann ein Problem wieder auf, das man damit gelöst hatte. Elegantere Lösungen sind überwiegend die, in denen man eine Mechanik durch eine schönere austauscht, in der dieses Problem gar nicht erst auftaucht. Das ist aber gar nicht so leicht, da man sich dafür als Designer erst mal von seiner ursprünglichen Idee loslösen muss. Also besser mit einem Minimum an Mechaniken beginnen und danach hinzufügen, was sich gut anfühlt.

Was bedeutet ein Minimum an Mechaniken? Unterschiedliche Spieltypen bedienen sich mehr oder weniger Mechaniken. Partyspiele oder kurze Kartenspiele bauen meist auf eine einzelne Mechanik auf. Dafür einen schnell verwerfbaren Prototypen zu erstellen, ist sehr angenehm und leicht. Schwieriger werden allerdings größere Spiele, Ideen, bei denen es mehrere Spielphasen gibt oder in denen man Mechaniken verknüpfen möchte. Beispielsweise wird in Magical Friends die Zugreihenfolge und die Kreaturenauswahl über eine Art Bietmechanik gelöst und das Spiel auf dem Spielbrett bedient sich einer anderen einfachen Mechanik.

Dabei hilft es sehr, wenn es Mechaniken sind, die man schon aus anderen Spielen kennt. Bietmechaniken gibt es in vielen Spielen, daran kann man schon vor dem Testen erkennen, welche Interaktionen bei der Mechanik besser und welche schlechter funktionieren könnten. Neue Mechaniken sind schwieriger. In dem Fall ist es hilfreich, wieder sehr simpel zu beginnen und sie nach und nach auszufeilen.

Gerade, wenn man ein größeres Spiel machen möchte, ist es sehr zu empfehlen, wenn man schon einige beliebte Spiele des entsprechenden Genres gespielt hat. Die Wertungen auf Boardgamegeek.com müssen nicht unbedingt den eigenen entsprechen, schaut man sich dort allerdings die Top 10 Spiele eines Genres an, wird man selbst, wenn einem die Spiele teilweise nicht so gut gefallen, einige tolle Umsetzungen von bestimmten Mechaniken finden. Es gibt Gründe, warum diese Spiele so beliebt sind. Versuche, sie zu finden, und überlege, ob sie für dein Spiel relevant sein könnten.

Nächste Woche werde ich dieses Thema fortsetzen, schreib mir einen Kommentar, wenn du dem Ganzen etwas hinzufügen möchtest. Ich und die anderen Leser freuen uns darüber.

Wenn du den Blog interessant findest, freue ich mich wenn du ihn abonnierst, das gibt mir Feedback ob Interesse dafür besteht.

Today, we continue where I left off last time.

Everywhere you read that a prototype should be cheap. Such a prototype should be easily discarded if it doesn’t work. It should not be complicated if changes need to be made. You will constantly replace and improve things. Additionally, mechanics should be added gradually. Furthermore, you don’t want to torment your testers—it would be good if the game already functions reasonably well when you invite testers.

There’s a lot to say about adding mechanics gradually. Generally, it is always easier to make a game progressively more complex and add a twist here or there, but making it simpler in certain areas is much more difficult. If a game is easy to learn but hard to master, you’ve definitely done something right. Striving for this is never a bad idea. Simplifying something afterward often means losing something for which a particular rule was introduced. Usually, a problem then resurfaces that had been solved by that rule. The most elegant solutions are those in which a mechanic is replaced by a more refined one that doesn’t introduce the original problem at all. However, this is not easy, because as a designer, you first have to detach yourself from your original idea. So, it’s better to start with a minimal set of mechanics and then add what feels right.

What does a minimum set of mechanics mean? Different types of games rely on more or fewer mechanics. Party games or short card games are often built on a single mechanic. Creating a quickly discardable prototype for such games is very convenient and easy. Larger games, however, become more challenging—ideas involving multiple game phases or mechanics that need to be interconnected. For example, in Magical Friends, the turn order and creature selection are resolved through a type of bidding mechanic, while the gameplay on the board uses another simple mechanic.

It is very helpful when mechanics are familiar from other games. Bidding mechanics exist in many games, and even before testing, you can already identify which interactions might work better or worse within that mechanic. New mechanics are trickier. In such cases, it is useful to start very simply and refine them gradually.

If you want to create a larger game, it is highly recommended to have played several popular games of the corresponding genre. Boardgamegeek.com rankings may not always match your personal preferences, but if you look at the top 10 games in a genre, even if you don’t love all of them, you will find great implementations of specific mechanics. There are reasons why these games are so popular. Try to identify those reasons and consider whether they might be relevant to your game.

Next week, I will continue this topic. Feel free to leave a comment if you want to add something—my readers and I would love to hear from you! If you find the blog interesting, I’d appreciate it if you subscribe, as it gives me feedback on the level of interest.

8 - How to Prevent Unnecessary Effort in the First Prototype (Part 1)

8 - How to Prevent Unnecessary Effort in the First Prototype (Part 1)

In this post, I’ll share my approach to creating a prototype, the missteps I made, and what I would do differently next time. There were several areas where I invested extra effort that turned out to be unnecessary.

It's widely advised that a prototype should be inexpensive, easy to discard if it doesn’t work, and simple to modify when changes are needed. Prototyping is an ongoing process of swapping out components, refining mechanics, and gradually adding new elements. Additionally, while testers should be challenged, you don’t want them to struggle with a game that barely functions—so ensuring basic playability before inviting testers is crucial.

In this first part, I’ll address the bolded points above. The remaining topics will be covered in one or more future blog posts.

Designing a Flexible Prototype

Some aspects of prototyping make implementation easier, while others present challenges. For instance, card and dice games are relatively simple to prototype—blank dice can be used to create custom faces, and game boards can easily be printed. Figures and cardboard standees are trickier but can often be sourced from existing games. Some games—like Magical Friends—rely heavily on visual elements for clarity. While prototypes don’t need to look polished, when a game features numerous distinct creatures on the board, maintaining clear visuals during testing becomes essential.

Here’s a mistake I made: I used images from the internet for my prototype. While this made it visually appealing right away, it created major limitations in testing. Copyright restrictions meant I couldn’t easily share the prototype or post photos online. If I were to develop another game, I’d either purchase a set of affordable stock images or find freely available graphics that I could legally use. Today, I’d likely generate these images using AI— when I created Magical Friends, tools weren’t as advanced. Ultimately, spending excessive time hunting for the perfect visuals isn’t necessary—at this stage, aesthetics should take a backseat to functionality.

An early prototype from 2019

A Good Approach: Avoid Creating 40 Different Creature Cards (with Standees) for Your First Prototype

For initial tests, a smaller number of creature cards is more than sufficient. Even if a full set is necessary to play the game properly, early tests can be conducted with shorter rounds. At this stage, the primary goal is to determine whether the game mechanics work and are enjoyable. Additionally, modifying something that affects all 40 cards requires an enormous amount of effort.

I’ve created prototypes for other game ideas before—some of which didn’t work—and I’m grateful that the effort put into Magical Friends wasn’t wasted. However, testing continued to be time-consuming, because I was reluctant to take a step back and simplify the prototype (which, in this case, primarily meant making it look less visually appealing).

That said, having a more elaborate prototype isn’t necessarily a bad thing. For testers, it can be nice to have a somewhat polished version even in the early stages. The real challenge is that modifying materials takes significantly more time than coming up with actual improvements for the game itself.

Despite all this, I’ll be keeping future prototypes simpler!

I have plenty more to say on this topic, but this post would become overwhelming. So, expect more soon! Do you have any thoughts or questions? Feel free to comment or reach out to me.

7 - Shipping and Warehouses

7 - Shipping and Warehouses

A third crucial factor in determining the selling price is shipping costs. Of course, one can handle the shipping personally and save some money, but there are many pitfalls. The more successful a project becomes, the more space is needed for full pallets and packaging cartons. While shipping and packaging materials might be slightly cheaper than using a warehouse, one should not expect significant savings for the considerable effort involved. Additionally, Kickstarter backers will also face some inconveniences.

That is why, for Magical Friends and How to Summon Them, I will definitely use warehouses that handle the shipping. These can be found online under Fulfillment Centers. One important aspect of shipping is customs. My manufacturer, Longpack, even offers direct shipping to Kickstarter backers, but the shipping costs to Europe and the USA are relatively high. While one could save part of the freight costs to warehouses (I emphasize "part" since excess inventory still needs to be stored somewhere), this is not enough to compensate for the lower shipping costs from a warehouse in the USA or Europe.

How many boardgames might be in there? Photo by frank mckenna on Unsplash

Moreover, customs can be quite troublesome for Kickstarter backers. If I ship my freight to Europe and the USA before distributing it to backers, I pay customs fees based on the manufacturing costs. For instance, I would be charged customs duties on €15 for manufacturing + freight. However, if I were to send the board game directly to backers in Europe or China, it might get stuck in customs, and buyers could end up paying customs fees on the €70 purchase price. Since about two-thirds of Kickstarter backers come from the USA and one-third from Europe, it makes sense to store the goods in warehouses—such as Quartermaster Logistics in the USA and Happyshops in Europe—before forwarding them to backers. If you request pricing lists, you will quickly notice that this approach results in much better shipping rates for the USA and Europe.

It is not uncommon for Kickstarter projects to partially subsidize shipping costs in certain regions. However, this must be carefully calculated. The final price should not exceed what backers are willing to pay. Customers usually resist paying more than 15% of the product price for shipping. The remaining shipping costs must be factored into the product price. Unfortunately, for customers outside of Europe or the USA, the price will be higher. However, if a Kickstarter campaign attracts a large number of customers from a specific region—such as Australia—it might be worth looking into an additional warehouse.

Shipping is a critical expense in any Kickstarter project, and miscalculations can quickly lead to financial issues. I hope this post has provided some insight into the topic! If you have questions or suggestions, feel free to leave a comment—it might help others as well. You can also send me a message.

One year after the Kickstarter:

Interestingly, the ratio of USA orders to European orders in my Kickstarter turned out to be closer to 1:4—meaning significantly more European backers. Many of my buyers came from local events and conventions, which likely explains the higher number of European supporters. I believe the more backers a project gains, the more the ratio shifts. Establishing a strong presence in the USA has been challenging for me. For a future Kickstarter, I might reduce the inventory shipped to the USA, as selling off surplus stock has been difficult, leading to additional storage costs.

Another point: Sometimes, I also send packages from home. Even for these individual shipments, sending them from a warehouse within Europe is still cheaper, despite the significantly higher effort involved. I’m not sure how things would look with a shipping contract for a larger number of packages.

At the moment, customs duties in the USA are also an issue—I hope there will be better news on this soon. Until then, this remains a challenging topic in the USA.

6 - Where can I find manufacturers, and who should produce my board game?

Upon request, I'll continue with the topic of pricing in this blog post. How do I determine the production costs of the game? Through quotes from manufacturers. And where can they be found?

There are actually plenty of manufacturers that produce board games, and not all of them are easy to find. To find some, I visited the booths at Spiel 2019 with my prototype and outlined which components I needed using it as an example. While I’m sure I missed many manufacturers, I managed to establish contact with 17 companies. That’s definitely enough for a good overview. Three were from Europe (Germany, Poland, and the Czech Republic), while the other 14 were from China. Of these, three never sent me a quote, leaving me with one German and 13 Chinese companies.

The first 14 quotes were overwhelming at first. So many different materials, various minimum order quantities, tiered pricing for print runs, special conditions for packaging and shipping, and sometimes even possible fulfillment services (shipping directly to Kickstarter backers—more on this in the next blog post). This led to prices that were not directly comparable at first glance. Usually, the prices are also listed individually for each component. To bring some clarity to the material chaos, it was time to pull out all the demo packages from Essen again.

Descriptions can initially be confusing.

Even though different manufacturers sometimes use different terms for certain things, the demo packages helped me get a clearer picture. Comparing the quotes also gave me an overview of which conditions are more standard in the industry and which are not. It also highlighted issues I hadn’t considered before that needed addressing with some manufacturers. With a second quote where I specified preferred materials, discussed any missing components, and standardized the print runs (e.g., 1,000/2,000/5,000 units), I was finally able to compare prices. And they vary widely—by about ±50% from the average price.

However, price alone isn’t everything. Communication with some companies was significantly better than with others. I had no board game references for some, and reviews from board game design groups and forums were a crucial factor in my decision-making. Some companies also specialize in certain components, such as miniatures, specialty dice, chips, coins, or game mats.

Deciding on one of the final five favorites was incredibly difficult. Panda has the best reputation in terms of quality and service but is very expensive and demands larger print runs. Other companies with bigger names were almost equally good in quality, offered significantly better prices, and provided excellent service. Ultimately, I chose LongPack. If something were to interfere, I could still fall back on Magicraft. Feedback on these companies is excellent, the prices are good, and communication was outstanding. However, the components needed and how comfortable one feels with a company may also play a role. The decision was truly tough and lengthy—370 emails were exchanged in total.

If you’re wondering what happened to the German company: I didn’t feel as comfortable with them. I also got the impression that they were reluctant to produce smaller print runs. The price was about 40% worse, even though some components were missing and not accounted for. Certain components made of other materials (e.g., plastic feet for standees) would still have to be ordered from China. Deluxe components for a special Kickstarter version would also have been significantly more complicated and expensive here.

Have you had experiences with board game manufacturers? I—and likely some of the readers—would love to hear your stories. Leave a comment. If you find this blog interesting, feel free to subscribe.

I hope this translation helps! Let me know if you'd like any additional support.

5 – How do you determine the price of a board game?

5 – How do you determine the price of a board game?

The common formula for pricing is:

MSRP = Landed Cost x 5

The “MSRP” stands for the Manufacturer’s Suggested Retail Price—that’s the price you typically see in stores. “Landed Cost” refers to the cost of production, including transport to your warehouse and customs fees.

An example:

Let’s assume the pure manufacturing cost is €12 (this usually depends heavily on the size of the production run). On top of that, you need to add the cost of transporting the game from the factory to you or your warehouse. Typically, the board game arrives shrink-wrapped and on pallets. Depending on where production takes place, this can be cheaper or more expensive. Customs duties may also apply. For this example, let’s assume transport and customs add up to about €4 per game.

(I'm planning a separate blog post specifically about shipping and logistics.)

That gives us a Landed Cost of €16.

Using the formula, the MSRP would then be €80.

That sounds like a healthy profit margin—but it's not that simple.

If you sell the game directly yourself, the profit margin really is good; you’d only need to pay VAT (which depends on your country).

However, ideally, you want your board game to be available in stores—and that’s where distributors and retailers come into play.

Retailers might pay you 50–55% of the MSRP, while distributors typically pay only 40–45%.

So from a €80 MSRP, you’d get only €32–36 from a distributor (who are usually your biggest customers), or €40–44 from a retailer.

Taxes still need to be paid from that, so your profit margin shrinks fast.

Also keep in mind: the Landed Cost only includes the printing and manufacturing costs.

Expenses for illustrations, marketing, additional services, and of course your own labor as a designer aren't included here.

So, in order to fund a second print run, you first need to sell quite a few copies from the first one.

If you have any questions, feel free to message me or leave a comment.

And if you have specific experience in this area, I’d love to hear about it!

What has changed since the first Kickstarter?

After talking with publishers, a new question came up:

What print run should I base my MSRP calculation on?

It makes a big difference whether you’re producing 1,000, 2,000, or 3,000 units.

The Landed Cost—and therefore the MSRP—can vary significantly.

It’s probably best to base your calculation on the smallest feasible print run.

This approach reduces risk for a Kickstarter and still allows publishers to offer better pricing for larger volume orders.

It’s all about careful planning—if your MSRP ends up too high, the game becomes less attractive to buyers.

Shipping quantities also matter.

Only a few pallets were sent to the US, and shipping cost me about €6 per game.

To Europe, I shipped a full container, which brought the cost down to about €3.50 per game.

Game size plays a huge role too.

A pallet might hold 1,200 small card games but only about 150 copies of Magical Friends.

That needs to be factored into your calculations.

Shipping speed is another consideration.

Shipping by sea from China is the cheapest, followed by rail, while air freight is very expensive.

Speed comes at a high price.

4 - Your Jobs as a Kickstarter Creator

While Kickstarter projects can be small-scale, if you aim to launch a board game that fits the market in terms of price and quality, there’s a lot to do. You can only set a competitive retail price starting at production quantities of 1,000 pieces (in some cases, 500 pieces). Selling that many copies is no easy task.

Many of these tasks can be handled by yourself, with friends, your team, or by hiring someone. The more people you pay, however, the higher the financial risk.

Business Management: If you want to avoid losses and make a profit (even a small one), you’ll need a company. Establishing a company entails several steps. You’ll need legal advice (e.g., for copyrights, trademark laws, taxes) and have to handle bookkeeping, plan income and expenses, and assess risks. In Austria, there is good support available when starting a business.

Game Design: You’re likely handling the game design yourself. What you’ll need, however, are game testers. While friends might be sufficient at first, you’ll soon require external testers and eventually blind testers, who test the game solely using the instructions. Multiple rounds of testing and revisions are necessary, with both voluntary and paid testers available. The tighter your project timeline, the more likely you’ll need to rely on paid testers.

Illustrators and Graphic Designers: Illustrations are crucial to bringing your game to life and creating its atmosphere, as well as attracting potential customers. While simpler art styles can also be effective, the illustrations must look professional. Hiring an experienced artist is a worthwhile investment. Graphic design is equally important. While some stunning artwork may need to be adjusted for clarity, a well-designed game is essential. Illustrations and graphic design represent one of the first significant financial risks before launching your Kickstarter.

Translators and Proofreaders: Spelling errors can appear unprofessional, especially in promotional materials such as newsletters and websites. It’s equally critical to ensure the quality of the game manual. Others should review your materials, and for the final product, a professional should thoroughly examine your game.

Manufacturing and Shipping: You’ll need a manufacturer and will have to gather quotes to find the right one. Collaboration with the manufacturer is key. To transport finished games to your storage or warehouses, you’ll also require a freight company. Your Kickstarter campaign helps cover these initial production costs.

Shipping: While assembling and shipping packages yourself is possible, a successful Kickstarter will demand more space and time. Fulfillment centers can take over storage and shipping, saving you considerable effort. Though this service is pricier, it minimizes logistical challenges.

Marketing: If no one knows about your game, no one will buy it. You’ll need a website or landing page to drive interest in your newsletter. Newsletters are essential for keeping potential customers engaged over time. A well-produced video and advertising campaigns (e.g., on Facebook) are necessary for your Kickstarter launch. Collaborating with bloggers and reviewers and showcasing your game at conventions are also effective strategies. Building interactions with potential fans is vital—they can convert into Kickstarter backers. Professional help can be sought for various tasks, but advertising represents another major expense before launching your Kickstarter.

Distributors/Retail: If your Kickstarter succeeds, you’ll need to navigate the retail market. Negotiations with retailers and distributors will be necessary.

Although you can outsource some tasks, you’ll still need to familiarize yourself with each step to accurately estimate costs.

During the Kickstarter Campaign: Everything comes into play, and the workload can easily become overwhelming. This period often brings a desire for additional support, with numerous offers from others—ranging from scams to genuine assistance. Be cautious, especially with promises of quick advertising results. If you’re exploring advertising support, it may already be too late. Researching reliable help in advance is advisable.

On a positive note, you’ll meet many people who genuinely support you, particularly in the areas of retail and distribution. Prepare for a social experience!

A team is super valuable!

I will get into more details with these jobs in the following Blog Entries

What experiences have you had with these tasks? Do you work in any of these areas? I look forward to your comments!

3 - Where does one start if they want to design a game?

3 - Where does one start if they want to design a game?

First, a disclaimer: What I’m describing here is based on my experience with board games and how I design them; I haven’t formally studied game design. Naturally, this post isn’t enough to cover every detail.

An idea is extremely important at the beginning, and two different approaches have worked very well for me: Top-Down and Bottom-Up.

Top-Down

This method starts with the big picture. I have an image in my mind. I know what the game should look like and what it revolves around, and I have an idea of how the atmosphere during play should feel. From there, I think about how to turn this image into a game, considering which mechanics would fit the theme. In this approach, the game is built around the theme.

Bottom-Up

This method works in the opposite way. You start with a great idea for a mechanic and figure out what theme would best suit it. The game is built around the mechanic. (A simple example: I want to have characters with unique abilities, which are auctioned off using a specific bidding mechanic. The core mechanic is fixed and serves as the foundation of the game.) There will be a dedicated blog post about the Bottom-Up approach in the future.

For “Magical Friends,” the idea came during a role-playing session. I imagined the social Bard gathering friends around him, while the Mage sat in his tower summoning and controlling helpers. During a lively Magician’s get-together, the Bard overhears a conversation and turns it into a competition. This idea led to my board game, which followed the Top-Down approach.

Next, I had to figure out the following:

What do players do during the game? (Summon creatures—or “friends.”)

What is the objective of the game? (To bring the friends to the party.)

These questions create a framework for the mechanics. Additional questions for this framework include:

How long should the game last?

What player count should it accommodate?

Should it be cooperative or competitive?

How complex can the game be?

Should luck play a key role in the game?

Where does replayability come from?

What kind of feelings and atmosphere should emerge during gameplay?

Don't forget the intended game duration and player count.

For example, I wanted "Magical Friends" to create a gameplay experience similar to "Smallworld." Simple rules, where the fun comes from chaotic gameplay. Luck plays a minimal role, and replayability arises from the wide selection of races and abilities that are randomly combined. Based on this, I designed "Magical Friends" for a playtime of about 1 to 1.5 hours and for four players (with more players, it becomes challenging to keep the chaos under control). It’s intended to be competitive and not overly complex. Personally, I prefer games where luck only influences replayability, meaning less reliance on chance.

If I focused on the mechanics without considering these questions beforehand, it could happen that a player is drawn to a board game by its theme, but then the theme gets lost during gameplay, leading to disappointment. Creating this framework in advance is helpful for me to envision what my mechanics need to accomplish. For example, I could come up with a great mechanic that works well for four players but causes too much frustration for seven players.

Don’t forget the intended game duration and player count.

Only then do I consider the mechanics of the game. Are there perhaps different phases in the game? Do multiple mechanics interact with one another? If I come across a mechanic that allows more players to join without negatively impacting game duration or chaos, fantastic!

No matter which approach I’ve taken, I now have a clear vision of my game—a core framework composed of the theme and a primary mechanic (game loop). This framework can be explained to others in a way they can understand. Even if early prototypes have some elements that don’t work perfectly, you know the direction in which you want to proceed. There will be a separate blog post dedicated to prototypes.

What has changed since the first Kickstarter attempt on this topic:

I’ve often thought about how, with my next game, I would already consider the production of components during game design. Or, at least, I would think about special components. Game cards, dice, or chips are not particularly relevant. However, with "Magical Friends," I realized fairly early on that a distinctive feature of the game would be summoning many different creatures. What I didn’t realize was the amount of effort required to bring 50 different creatures into the game. I only gained this experience through creating prototypes and discussing them with manufacturers. As I reduced the amount of rounds played and increased the creature count, its possible to play the game with 5 players. Testing showed that 4 and 5 players are even the best player count to play.

In the Meantime also the story changed a little bit, altough its still similar, the bard has dropped and its a wizard and witch competition.

Please leave a comment if you have valuable insights to share about this point. I, and other readers, would surely appreciate it!